|

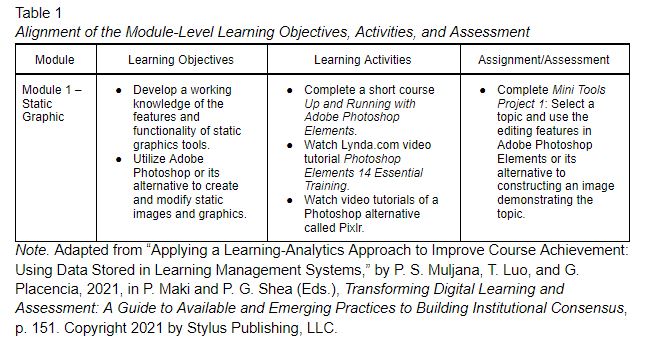

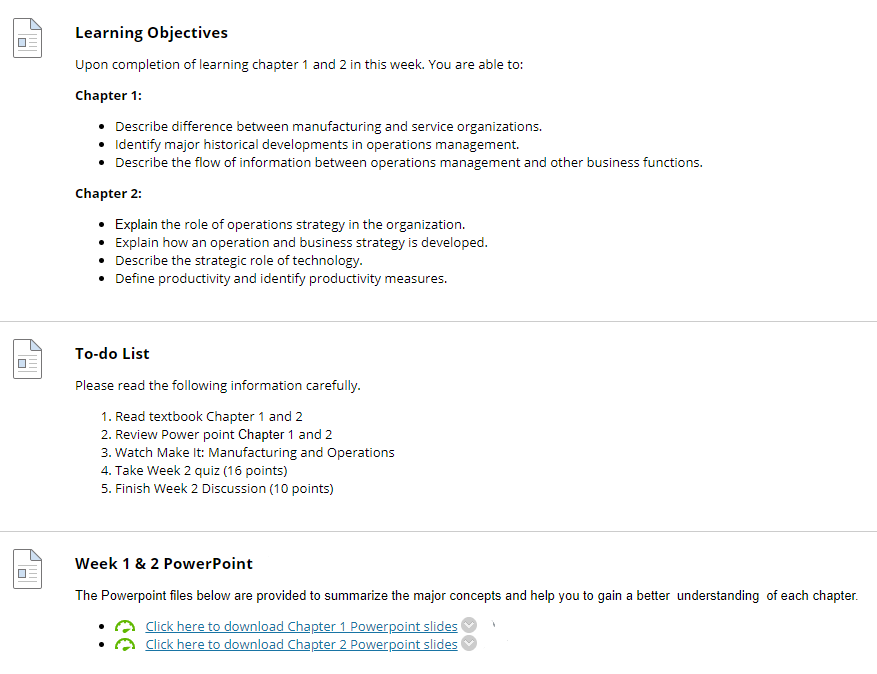

As more and more instructors are designing courses in their institution’s learning management system (LMS), there is a need for these online course components to be well-designed and student-friendly. We are practitioners and scholars from the Instructional Design and Technology (IDT) field, proposing streamlined guidelines, called the Three-Tier Design Process, for designing and developing a course in an LMS. A paper describing the guidelines has recently been published in the journal College Teaching. This blog entry presents a brief description of the three-tier design process, who can use it, and what each tier includes. What is Three-Tier Design?Drawing from existing theories, models, and literature in the IDT field, the three-tier design process (TTDP) was developed to help faculty promote positive learner-centered experiences. While there are many instructional design (ID) models used to practice course design, the TTDP is not intended to compete with those ID models. The TTDP consists of three considerations for designing and developing a course in LMS that we call streamlined guidelines for creating effective learning experience and easy to use environments for all students. By following the TTDP, the course materials in an LMS can be presented in an organized manner. Students can enter the course using an LMS and know where to start, how to navigate, find specific materials, and understand the expectations without providing long explanations. Faculty and teaching assistants (TAs) without formal education in instructional design and learner-experience design will find the streamlined guidelines useful and practical. Practicing instructional designers in higher education may also use the TTDP for introducing course design to faculty and TAs. What are the Three Tiers?Tier 1: Design “Tier 1 focusing on the design … serves as a firm foundation for the next tiers” (Ji, Muljana, & Romero-Hall, 2020, p.2). In this initial process, considering the alignment of learning objectives, learning activities, and assessments are crucial. One way to help accomplish this is by creating a table where course-level learning objective(s), module-level learning objectives, assessments, and learning activities are listed juxtapositionally. Table 1 displays an example of aligning module-level learning objectives, activities, assessments. When writing learning objectives, referring to Bloom’s taxonomy and SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-Bound) objectives are helpful in identifying measurable learning outcomes. A list of learning activities should include clear instructions and relevant examples. Designing these course elements (i.e., learning objectives, learning activities, and assessment) with accessibility in mind will promote equal access to the information within the course materials. For example, if a learning activity involves watching a video, the selected video should include a closed caption. Tier 2: Development Tier 2 revolves around the course development process in an LMS. During this process, course materials are usually ready to be added to the LMS. Faculty and TAs may consider using concise language and/or bullet points rather than descriptive language. Therefore, students can easily read and skip to the area they need to locate, providing ease of scanning to students, especially those with reading disorders. Instead of listing all materials, the course content can be categorized and organized into meaningful segments, such as modules. A module may consist of a list of learning objectives, a to-do list (a list of learning tasks), learning materials (e.g., any slide presentations and/or other relevant documents pertaining to the modular topic), link to a discussion forum, link to assignment or quiz, and any examples for an assignment (see Figure 1). This will allow students to find what they need to complete the module. Figure 1. A screenshot of a partial module page displaying the learning objectives, to-do list, and lecture slides for the respective module. Adapted from “The Three-Tier Design Process: Streamlined Guidelines for Designing and Developing a Course in a Learning Management System to Promote Effective Learning,” by W. Ji, P. S. Muljana, and E. Romero-Hall, 2020, College Teaching, Advance Publication, p. 9. Copyright 2020 by Taylor and Francis Online. Tier 3: User-Experience Considerations The steps in Tier 3 can further promote the user-experience aspect of the course site, such as ease of course navigation, easy access to resources, and communication from faculty or TAs. Boosting the ease of course navigation can start with providing a brief course tour or a “Start Here” page that the instructor expects students to visit first to introduce the course menu and layout. If the course incorporates the use of specific technologies (e.g., software), providing access to technical resources, such as links to tutorials and manuals of the software, is helpful for students. Therefore, students will not have to spend time searching for these resources; instead, they can use their time for studying. Faculty and TAs may want to ensure that their contact information is included accurately. Their schedule (e.g., office hours) may change each semester; therefore, updating this information helps students reach out to them successfully. Faculty and TAs may also provide multiple ways for students to contact them. Providing email etiquette can promote productive and efficient communication, such as how students should address the faculty or TAs, write the email subject, include the course ID or name, among others. ConclusionFacilitating learning is about successful communication exchanges. Instructors attempt to send the ‘message’ to students and hope for a mutual response from them. However, ‘noise’ can hinder the communication process. The TTDP helps reduce these unnecessary ‘noises.’ As a result, students can identify the learning actions they have to conduct. The ID process can be complex; the TTDP is intended for those without a formal education in ID to manage the complexity of promoting positive learner-experience through a user-friendly course site in an LMS. Article and AuthorsJi, W., Muljana P. S., & Romero-Hall, E. (2020). The three-tier design process: Streamlined guidelines for designing and developing a course in a Learning Management System to promote effective learning. College Teaching. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2020.1865253  Weiwei (Will) Ji is an Instructional Designer and an adjunct faculty member at Arkansas Tech University. He can be reached via email and LinkedIn.  Pauline Salim Muljana is formerly an Instructional Designer at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. She is currently a PhD candidate in the Instructional Design and Technology program, Darden College of Education and Professional Studies, at Old Dominion University. You can connect with her via Twitter, LinkedIn, or her personal website.  Enilda Romero-Hall is an Associate Professor in the Department of Education at The University of Tampa. She is also the Graduate Coordinator of the Instructional Design and Technology program. You can connect with her via Twitter, LinkedIn, and her personal website

0 Comments

Alex Serna & Jee Deogracias When you walk into the middle school summer program for any of Breakthrough Collaborative's 24 affiliate sites across the country, whether in Miami or Sacramento, you immediately recognize something unique and special. In San Juan Capistrano, if you walk into Sillers Hall, where students and staff gather to eat, you'll be taken aback by 136 students cheering and chanting in unison (let's be honest, these are middle school students who in their natural environment aren't the most inclined to want to do cheers). It is quite a sight. That energy and community never falters throughout the six-week summer program, which aims to reverse the summer learning slide, prepares our students for college, and builds community. In addition to supporting highly motivated, traditionally underrepresented students, Breakthrough also empowers and trains college-aged students (referred to as “teaching fellows”) to become the next generation of educators and advocates. Going into our 2020 summer program amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, affiliates were forced to find alternatives to in-person programming. The situation left Breakthrough leadership with a huge challenge: how do we recreate the energy, spirit, and community of a 40-year-old, in-person program to a virtual setting? Like many others who embarked on online learning for the first time this past spring, we were initially apprehensive. Several critical questions were looming which would determine the program’s outcome: Will students show up? Will they show up consistently? Will they have technology tools at home to participate? Will we prepare students for the fall and beyond? Will teaching fellows feel impacted by the experience? These concerns were especially salient considering local and national reporting and research that indicated low student attendance rates and engagement, especially among historically underrepresented students, when school districts switched to remote learning in the spring. With agility, fortitude, and positive spirits, Breakthrough staff across the country not only reimagined core components of a traditional Breakthrough summer but also developed creative alternatives to best meet the needs of both students and teachers. While the summer wasn't without its challenges, we found many examples and lessons learned to celebrate and share. Our newest white paper, "Breaking Through the Distance: How Relationships Foster Online Learning," summarizes our key learnings as six strategies that educators and others can use to best position their students for success during virtual learning. We share our strategies below: Strategy 1: Believe that online learning is possible.

In reflecting on summer 2020, it was somewhat surprising to discover how powerful the relationships were by the end of the virtual summer, but also exciting to know that the essential elements of a Breakthrough program are still as powerful online as it is in person. As one student remarked, "Despite having a different environment this year, every class still had a sense of community." In many respects, we were able to re-create the energy and community reminiscent of Sillers Hall virtually. The Collaborative’s successes are evidenced in the data; by the end of the summer:

Alex Serna, M.Ed is the Executive Director at Breakthrough San Juan Capistrano. He can be reached via email ([email protected]) and LinkedIn (https://www.linkedin.com/in/alexserna1/). Jee Deogracias, Ph.D. is the Director of Research and Evaluation at Breakthrough Collaborative. She can be reached via email ([email protected]) and LinkedIn (https://www.linkedin.com/in/jee-deogracias). Read the full Breakthrough Collaborative white paper at this link: https://www.breakthroughcollaborative.org/white-paper/ Drawing on several strands of literature, this study develops a comprehensive survey that systematically collects information on online college instructors’ use of instructional practices that the literature suggests are promising in promoting interactions in an online setting, as well as instructors’ perceptions of online education. We administer the survey to all online instructors at a large community college and examine how reported frequency of interaction-oriented instructional practices may cluster to form meaningful groups of instructors. K-means cluster analysis distinguishes between two profiles of instructors–a high-practice user group and a low-practice user group. The high-practice user profile is predicted by more teaching experience, greater self-efficacy for using learning management systems, and greater perceived benefits of online learning for students. The findings have several implications for future research examining pedagogical behavior, as well as the design of professional development activities aimed at enhancing the use of effective online instructional practices among college instructors. Read the full paper here. Address correspondence to: Gabe Avakian Orona, [email protected] Galvanizing family and community action in support of children's schoolingBy Yenda Prado |

Want to write for us?Send us an email with your ideas to olrc.uci.edu Archives

February 2021

Categories |